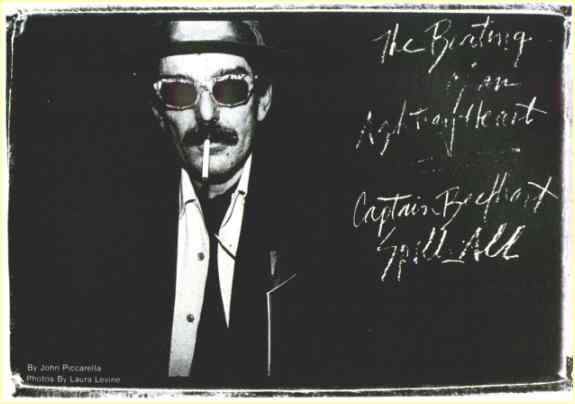

Whatever the relationship between the music of Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart) and new wave, it must be more than coincidence that after fifteen years as a largely ignored but legendary eccentric, he is making music that is as strong and strange as any he has ever made, and is receiving more recognition than ever before. Captain Beefheart has always represented the final frontier of rock weirdness, but his vintage records were only taken seriously by a few at the time of their release. Few critics (Langdon Winner foremost among them) tried to negotiate the maze of the music’s roots and the essence of Beefheart’s ability to transform the elements of pop music into an otherworldly language.

The first Magic Band, which recorded Safe as Milk (1967), Strictly Personal (1968) and Mirror Man (recorded 1968, released 1970), was a wild electric blues outfit that presented in pop / psychedelic form the contorted guitar rifts and growling vocals that are the essentials of Beefheart’s music. But it wasn’t until Van Vliet was assured complete artistic freedom on Frank Zappa’s Straight Records that he fully realised his conception. He composed the twentyeight tunes for Trout Mask Replica in one day at the piano, and then spent a year at his home in the California desert, teaching the material to his new band which included Drumbo (John French) and Jimmy Semens from the original group as well as Zoot Horn Rollo, Rockette Morton and The Mascara Snake. With Zappa producing they recorded the double-album rnasterpiece, Beefheart laying down the vocals without headphones to hear the backing tracks.

The crucial difference between Trout Mask Replica and the earlier records was Beefheart’s total control over the band. A band usually works off the lowest common denominator, the beat; but a blues singer, with just a guitar for accompaniment, can break up the beat according to the jerks and starts of his feeling. This is how a Robert Johnson or a Son House would render a song, with the whims of the wrist offering spontaneous counterpoint to the vagabond voice. Through note-for-note composing of all the instrumental parts Beefheart was able to orchestrate this process, and that is the magic of The Magic Band. Rather than work as individuals off a common pulse, they move, by a combination of fascism and telepathy, through the Captain’s personal rhythms. In this way he was able to arrange four or five different melodic compliments, worming around each other within the twisted unison of his jagged musical motion. Though one can readily identify rock and roll in the electric instruments, Delta blues in the vocals and slide guitars, surrealism in the lyrics, and free jazz in the horn solos, the juxtaposition and recombination of these elements is so original that the whole process of classification is thwarted. And one can understand why a genius of this magnitude dismisses the question of influences.

The classically-minded mallet work of Arthur Tripp III (Ed Marimba) was the added element that broadened Beefheart’s palette on Lick My Decals Off Baby, a more concise and lucid distillation of the Trout Mask style. Personnel shifts, stylistic changes and a gradual attempt at commercialisation of Beefheart’s sound by various producers characterised the next few albums until the Magic Band broke up after the hopelessly compromised Unconditionally Guaranteed in 1974. The Spotlight Kid (1972) saw Beefheart introduce keyboards, revert from saxophone to harp and a bluesier feel, and top the sound with stinging guitar leads by Eliot lngber (Winged Eel Fingerling). Roy Estrada (Orejon), of The Mothers and Little Feat, took over bass and Rockette Morton moved to guitar for Clear Spot (1972). The album featured a horn section, backup vocalists and some gorgeous ballads, and achieved a unique Beefheartian rhythm and blues, rhythmically sparked and well produced.

It wasn’t until six years later when a new Magic Band was formed, again from former fans, again with Beefheart in total control of every note, that he recovered his complex excellence. The band’s first LP, Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) in 1978, was recorded with a presence and clarity that none of the earlier albums had. The combination of Tripp’s marimba, Eric Feldman’s keyboards and Bruce Fowler’s trombone woven through the revitalised two guitar riffing (by Richard Redus and Jeff Tepper) redefined the sound.

Now the band’s newest record, Doc at the Radar Station, refocuses the central angular guitars of Tepper and Drumbo in stark relief. Produced completely by Beefheart and done mostly without overdubs, horns and percussion pared down to a few integral colourations, the two slashing guitars etch out a rough surface. Mellotron, synthesizer, French horn and piano offer symphonic relief like an orchestra phasing in and out of the airwaves with the band. There are two brief instrumentals, a solo guitar piece and a duet for guitar and piano. Beefheart hasn’t worked with such spare materials since the similar tracks on Trout Mask and Decals, and his vocals are more spirited than ever. While jazzy bass clarinet and marimba dance around modernist orchestral passages on the album’s final cut, “Making Love to a Vampire with a Monkey on My Knee,” he delivers his most powerful line ever: “God, please fuck my mind for good.” For the uninitiated this Doc at the Radar Station may accomplish just that.

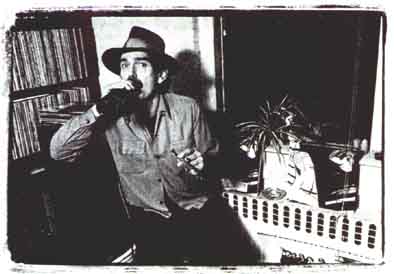

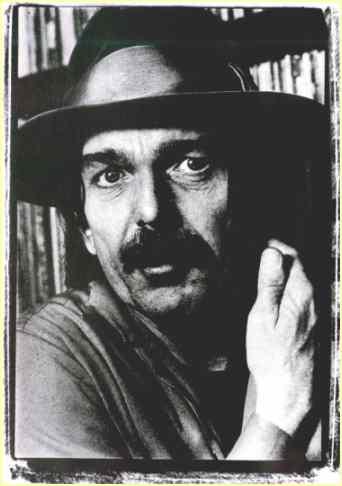

Spending time with Don Van Vliet isn’t much different from listening to his music: he opens his mouth and you’re on acid. I interviewed him at the home of Gary Lucas, who plays “Flavor Bud Living,” the solo guitar piece on the album, and his wife Jan, who is Beefheart’s manager. While we waited for Don and Jan to arrive I was entertained with Beefheart outtakes, a great one from Clear Spot that should have been on the album and one from The Spotlight Kid that rightfully wasn’t. I was shown a TV commercial for Lick My Decals Off Baby which was banned because someone thought the title was obscene. I also saw some of Beefheart’s artwork, including a drawing done in the dark during a performance of the Peking Opera. The interview began while everyone was talking and at various times Ling, Gary and Jan joined the conversation.

Captain Beefheart: Gossip, man. Tape.

Captain Beefheart: Gossip, man. Tape.

New York Rocker: Funny how everybody stops talking.

CB: Do you blame us? After Nixon? Yeah, he scared me. he was so hip… Well, I don’t know. I don’t like the imitation of Ed Sullivan that much …. That was it, man! Ed Sullivan was a funny cat… OK, ask me a weird question;

NYR: No, let’s not start with the weird questions. (Phone rings)

CB: That song I did is right, isn’t it?

NYR: “Telephone”?

CB: Yeah plastic horned devil!” Let’s see, I’ll show you … I mean, really! (Picks up receiver and replaces it upside down) Look at this!

Gary Lucas: It’s like a plastic horned devil – a grey udder.

NYR: Great album, by the way.

CB: Oh, thank you. It is good, isn’t it? I think maybe the best I’ve done.

NYR: A lot of people are saying that…

CB: No, but…. the best I’ve done…. I’m not even done… finally hit a clear spot. I did the whole thing… everything; and that’s the way it should be because that’s a true representation of that band.

NYR: But it’s not the first album you produced yourself. You did Decals yourself.

CB: Oh, yeah. Yeah, I even fired somebody when I did that.

NYR: Who?

CB: Dick…

NYR: Kunc?

CB: Kunc… I had to. I mean, I can’t go back to the past. I haven’t any idols and what I do is what I do. Anything else doesn’t work. Isn’t that odd?

NYR: Yeah, you’ve often said you don’t have many influences.

CB: None.

NYR You must’ve in the beginning.

CB: No.

NYR: But the early Magic Band was a very blues-based thing.

CB: But I don’t. .Well, “Electricity” IS blues, y’know, “Singing through you to me/Thunderbolts caught easily/Shouts the truth peacefully/Electricity.” Blues is obvious.

NYR: “China Pig.”

CB: “China Pig” was… you know what that’s about? It’s about a human being, how fragile a human being is. I mean the body as opposed to all the forces. I mean. . . it isn’t easy. Have you ever been injured?

NYR: Yeah, I got hit by a bus…

CB: Ooooh man!… Glad you made it. Really?

NYR: That’s why you don’t live in the city, right?

CB: I don’t live in the city because I don’t need all those extraneous noises. They just absolutely…I mean, I feel like a puppet, y’know… my ears, I’ve developed my ears, or they were developed and here I am with ’em. Look at that! Three and a half inches long, man! . So it traps a lot of. .. trouble.

NYR: I wanted to ask you about Clear Spot. Did you intend to do sort of an R&B record and get Ted Templeman with that in mind, or did he come and lay his arrangement thing on top of what you did?

CB: His arrangement thing?

NYR: You know. ..the horn section, backup vocals-

CB: I did that! Blue Mitchell played on that thing. Do you know who that is, man?! Ted Templeman had nothing to do with it.

NYR: He just had his name on it?!

CB: Yeah.

NYR: He wasn’t in the studio?

CB: He was there… I guess…

Gary Lucas: Tell him what he said about the harp thing on “Nowadays a Woman…”

CB: “You wanna do that over?”… That was what he said… I said, “Absolutely not. That’s correct!”… I mean my baby won’t let me have a baby. My artist won’t. I mean that’s it. That rejected it. . . shouldn’t be there. I think an artist is one who kids himself the most gracefully. ..That’s what I do. I like to tease myself.

NYR: Do you kid yourself about not being influenced by anything? Is that a tease?

CB: No…my baby rejects it immediately and that’s it.

NYR: But the music has gone through certain stylistic changes…

CB: Oh. ..according to myself though, you see.

NYP: But at that time Clear Spot seemed to pick up on a rhythm and blues type of feeling.

CB: Really?

NYR: Like “Too Much Time,” which is a great vocal performance, sounds a lot like an Otis Redding stylisation to me.

CB: (To Lucas) He wishes.

Gary Lucas: The single that was released from that album was in the charts in Boston.

CB: Until they found out I was…

Lucas: White.

CB: Well, I don’t know about white. Everybody’s coloured or you wouldn’t be able to see them. I put that in Rolling Stone—l don’t understand those kinds of things. I know nothing of any of that. There’s a lot of things I don’t understand.

CB: Well, I don’t know about white. Everybody’s coloured or you wouldn’t be able to see them. I put that in Rolling Stone—l don’t understand those kinds of things. I know nothing of any of that. There’s a lot of things I don’t understand.

NYR: The new album is very guitar-oriented. You haven’t done that in a long while.

CB: Yeah, I like guitar.

NYR: Well, you’ve always used the guitars as the rhythmic base, but you used to have all these marimbas and different horns coming in and out, and you really cut that down this time.

CB: Yeah’-.a skeleton crew… but I like all of the other things.

NYR: On the last album, Shiny Beast, you did it all, it was realty orchestrated.

CB: I like that album.

NYR: I like it, too… and this one was a real surprise because it’s real direct.

CB: But I got the same thing down, I think. And I’m even thinking, on the next one I’ll use just two guitars… maybe no drums. –maybe… I mean on certain things.

NYR: Well, you have those two instrumentals on this record… The instrumentals you’ve been doing, like on the last record, were with the whole band. .and here you’ve got a solo guitar piece…What made you decide to use the trombone and marimba on only one cut?

CB: Artistically that’s the way I thought it should be. Only that. For no other reason. You see it required it. Whatever the music was in my head, that’s the way it was, same as putting a line on a painting or a drawing. It’s just music sculpture. Then again I don’t know, really… y’know, I don’t know.

NYR: That’s a great drawing.

CB: Thank you. Yeah… that was a great opera.

NYR: I didn’t see It.

CB: You should have. Really, though… I mean Peking! When are they gonna do that again?

NYR: Yeah, and you can’t just go to Peking—

CB: I don’t now, I’m g’onna try Those people are excellent musicians.

NYR: You didn’t find yourself influenced?

CB: No… I mean I wouldn’t do that. It isn’t my right. I am my own artist. It wouldn’t work. But I listen…Totally listen. I’m able to do that, I’m totally able to just listen. You know that isn’t easy. I’m lucky that I’m able to do that. I heard it. Ooooh, did I hear it.! The thing that annoyed me was the public clapping, you know, like in all of the wrong places… Listen, they don’t show them like that over there. They have tents and they eat during the thing. Three days, they go.

NYR: It wasn’t an entire opera, right? It was a Greatest Hits…

CB: No, they cut it. And the thing is they had to. They showed it in a show…I mean, a theatre. Everybody was acting like they do at the Rose Bowl. They have a fireworks display and every time a firework goes off they go “OH!” It was horrible. Really, really rude. I didn’t say anything. It was really corny, like that cheap perfume that adheres to the plastic of a telephone receiver. One-dimensional. And there was a lot of perfume in there … People don’t like the way they are… And I wonder if women don’t do that because men. I’m not saying you or myself… but what are they doing? I mean, they like that? I break out in a horrible rash if I use a telephone in the city. I can’t stand it. I think it’s fascist. Very fascist odor on a telephone receiver. – – What’s that?

NYR: Sound of the city… construction work.

CB: It’s pretty good.

NYR: It’s got a rhythm.

CB: It’s pretty good.

NYR: There are a lot of good rhythms in the city. But you were saying before that you didn’t like all that

CB: But I’m not directly in the city. This is an older part, isn’t it? Cobblestone. There’s a bar down here… I hate to say it. It’s horrible… I mean, Dylan Thomas.. The White Horse… I mean, the White Horse isn’t quite the way I think it should be. Of course, why am I assuming it shouldn’t do something other than what I think it should? Because I’m an artist? Because I shit tie-dye? Van Gogh – I’m gonna see him soon… When I go to Holland.

NYR: Did you see the Picasso show?

NYR: Did you see the Picasso show?

CB: They wouldn’t let me in. They said it was only for foreigners and I said, “I’m pretty foreign.”

NYR: That reminds me.. – On the last album, on “Tropical Hot Dog Night” and “Candle Mambo” you had a South-of-the-Border sound…

CB: The baby was South-of-the-Border that night.

NYR: ..kind of a mariachi sound. Where did you pick that up?

CB: Oh, I have all of that – – – and then some… I do. I mean, it’s there, it’s all there.

NYR: You do listen to music, though?

CB: Did I ever listen to music? Yeah – I like to listen to music. But I won’t trace. I won’t go over something out of respect. What do you listen to?

NYR: Lots of things.

CB: You play guitar?

NYR: No, bass.

CB: Bass is nice… I once used “air-bass”-did you like that?

NYR: You mean the trombone thing?

CB: With an octave divider, yeah.

NYR: He’s got in the band now?

CB: Yeah, Bruce Fowler… He’s a real good friend and he could be there or he won’t, y’know.

NYR: When you’ toured last time he was with the band.

CB: Yeah,, – I like Bruce. He’s good. I think he’s one of the best. I don’t know what to say about him other than I can go.. (whistles wildly)

NYR: And he can play if…

CB: Immediately.

CB: Is that how you teach a song to the band? You don’t write it out?

CB: Well, I could…and play the piano. I play all of these things – you didn’t know that?

NYR: But you teach all the instruments by playing the parts on the piano?

CB: You can do it on the piano… you can do it on guitar some times.. Sometimes on the mellotron….sometimes on the Moog. I like mini-Moog, I think that’s a real sensitive instrument.

NYR: You never let the players improvise?

CB: No, because I’m the artist. That comes out of me. I’m the composer. Very strict.

NYR: Where did you get your horn style? Your solo style?

CB: I just paint through it. I don’t know where I’ll show you a rehearsal exercise. This is the only rehearsal I do on that horn. (Lights a match and holds it up letting if burn down) I got too close the other day. Only I’m trying to get where I’m really doing it. I’m trying to light a cigarette while I’m having a conversation with myself. I wait until a certain….. and then before it burns, just when it heats up, then I’ll light it and that is my rehearsal – you ever do that?

NYR: No.

CB: But I mean think about it….are you sure? But you ought to think so. Don’t you?

NYR: I like sax…

CB: I mean alto, though.

NYR: I like tenor.

CB: Not him? (gestures in the air)

NYR: Who?

CB: Oh, the guy who came through the skylight. Charlie Parker. Ooooh, what about that guy?

NYR: Oh, yeah. You like that?

CB: Oh, yeah!

NYR: Now we’re talking.

CB: You like that?

NYR: Oh, yeah.. you like Albert Ayler too?

CB: Not ever that much…

NYR: You don’t like his marching things?

CB: Oh, I enjoyed him…I don’t like marches. You know why?… I’ll tell you why: war. It’s very similar to disco.

NYR: But there’s another kind of march, y’know, street parade..

CB: Oh, you mean Philip Sousa… yeah, that’s pretty good!

NYR: I think “Candle Mambo” is like that, with that trombone thing..

CB: I do know what you mean, yeah – – – and also the drums. Right… well, do you know what that was… hounds rhythm.. .(bends over imitating gallop) that’s what did that to me.

NYR: You take visual motions and put them into rhythm all the time–

NYR: You take visual motions and put them into rhythm all the time–

CB: Like that. (Snaps fingers)

NYR: So you’re not kidding about that, when you talk about sculpting into sound? it really does wor.i that way?

CB: Yeah!.. and music gets in the way. I don’t like music. I really don’t. I’m a sculptor.

NYR: You like your music. You like this record.

CB: No I don’t. I’ve listened to it a few times. That’s it. Like getting your wing caught if you’re flying. Too much of it is sickening. And that happens to me like that. So it’s a real exercise in boredom.

NYR: You like Charlie Parker, though?

CB: Yeah, but you see I didn’t have to be there, throughout… You see I wonder if he liked Charlie Parker.

NYR: He had a rough time.

CB: I think maybe he had an irritation in time. I mean he was irritated. I mean he created irritation. I think in a lot of ways he may have been a sculptor.

NYR: Coltrane.

CB: I knew John Coltrane. I mean I knew him. I liked him, he was a nice man.

NYR: Did you hang around jazz circles at that time? You knew Ornette?

CB: You see, I never… I was always the person. The music was just… I mean it was the individual. Oh, I loved Roland Kirk… for years. We were friends.

NYR: Did you ever play with him?

CB: Oh, no. I just enjoyed what he does. How could I? How could I play with him? How could he play with me? Although we were real good friends. Total respect. I think he’s the most underrated American musician of all.

NYR: “The Best Batch Yet”- what’s that about?

CB: They are cardboard balls seamed in glue, overwhelming technique, done from the inside where you can hardly see, done through diligence… y’know, they’re just balls floating across the music. I mean very, very tapered. Just a poem. But who’s ever said that?.. They’re pearls, you know… uh, that music on that thing – do you like that?

NYR: Sure— You’ve heard Pere Ubu?

CB: I don’t have to.

NYR: I think they use that kind of rhythm a lot.

CB: Do you? They don’t know what I’m doing…

NYR: Maybe they don’t, but they use similar rhythms.

CB: They try. And it they use that rhythm… Nobody else but me has used that rhythm. I guarantee you, ’cause it comes out of me. A lot of people think I don’t know about rhythm…

NYR: Who thinks that?

CB: People who think too much. I mean, everybody has their own rhythm… I don’t need it. I have my own rhythms. It’s very selfish, what I do. I’m an artist.

NYR: Do you think this album is in any way a response to the people you’ve influenced? To the new wave?

CB: Not at all. No, I could care less. Really. I don’t even listen to….

NYR: “Ashtray Heart” isn’t addressed to–

CB: No.

NYR: Well, it sounds like that: “You used me for an ashtray heart,” like “you know you made me into this”—

CB: I’m talking to my baby. My artist. What it is that makes me get up in the middle of the night when I haven’t had any sleep and I’m really fatigued or dazed like I’m five days awake… that span of time and I finally get to sleep and all of a sudden… Bing!.. – y’know, a piece of clay or a pen. It’s ridiculous. I’ve had times when I didn’t sleep for a year and a half. That’s a fact. I couldn’t. I wrote down everything. Everything! What it was to me was a mental fast. Because to get rid of – y’know, getting it all out. Like an illness or a fever, burning off… In nature, a fire burning everything away and then coming back with new things. Ooooh, I’ve been through it.

NYR: Do you know what “a case of the punks” means in that song?

CB: No. But do you know anybody who has a lot of money that would come out with a new product? “A case of the punks-” it may be funny, though. I think… well, then it could mean that, couldn’t it? It could be that they lost sight of – – – and became a product, y’know, a case…

NYR: That’s what I thought you meant.

CB: Well, I did and then again I didn’t, I meant other things. I’m not being evasive. The thing is that it means a lot of things, try and not have it just one fixated thing. But then again I’m not gonna go, “Well, this is art…”

NYR: Do you feel, as an artist, that there shouldn’t be an interaction between you and the culture you’re addressing? You have fans that are in the rock culture. They have bands. There are connections that exist. Do you think that should be avoided? Everyone should do what they do? Or should there be some relation between you and what’s going on?

CB: I think everybody should do what they do… Because wouldn’t that be interesting? The, as an artist, I could go out and hear something that has nothing to do with me, which is so pleasing… The Chinese opera was wonderful…

NYR: Yeah, they’ve never heard Captain Beefheart. Isn’t an artist in some way representative of his culture?

CB: At times, but isn’t it funny I’m not that representative of it?

NYR: I think your work is very American— like I was saying before about the blues. Did you listen to a lot of blues when you were younger.

CB: You know I didn’t. I was sculpting. I used to lock myself in. My mother would have to put food under the door, like a cat door, ’cause I was in there, man.

NYR: On TROUT MASK you did those solo vocal places which you’ve never done again, like “Well” that had a real old blues feeling, like a field holler–

CB: Yeah, who said an albino can’t have soul? What I’m saying Is that I think a poem like “Well”… – and I have that voice. Where did it come from? Ooooh, If I were to think of that… I have an awfully powerful voice. I haven’t heard the likes of it. Although If I could parrot… WHAT? I’d feel so funny, like putting on a sleeve of someone else’s coat… It is fine. I have seven and a half octaves. I actually do. I don’t know how. Why? Because I never went to school. And never did I train myself.

NYR: Did you practice singing?

CB: No, I don’t… at all, I don’t rehearse anything.

NYR: Except the band.

CB: Oh, yeah. But they love it. If they didn’t, they’d leave. And they do. Some do.

NYR: Drumbo just left again, right?

CB: Yeah… Fine. He’ll do something else. I don’t wanna restrict anyone from leaving. I have a great fellow playing guitar. You have to hear him. The fellow who came to me after Drumbo left…

NYR: Whet kind of a sense of your audience do you think you have?

CB: Probably very honest, because I’m doing what I’m doing solely… I don’t want to bother ’em… I don’t mind if they come there.

NYR: You certainly hope they do.

CB: No, because I don’t want to control them. If they want to see me, I think that’s interesting. I appreciate it. Because I can do more… That’s amazing. They could go somewhere else… and I was gonna say, they often do. But how do I know that? I wouldn’t be able to be doing my art. That’s selfish.

NYR: Do you feel like you’re communicating?

CB: I m not an entertainer. You know that.

NYR: You¶re doing it for people? You re doing it to tell them something?

CB: Not really. No, I don’t like politics, do you? But what would be better? Ooooh, do you know what I mean? I mean I don’t think it’ll work, but I just think people should help themselves and really worry about every place they put their foot, because there’s something living there.

NYR: You’re still very interested in ecology?

CB: Oh, yeah. I think, if anything, that’s my instruction.

CB: Oh, yeah. I think, if anything, that’s my instruction.

NYR: Do you worry about the world political situation?

CB: It is scary. Oh, it’s so stupid. Oh, it’s corny… for an observer. It’s really corny isn’t it? I mean, why do people step on other people? They wanna get there before the other person gets there. I mean, it’s an exercise on the streets of Manhattan… “White ants runnin”‘ – remember that?

NYR: Yeah… I don’t remember where it’s from.

CB: No you didn’t? Yes you did. Isn’t that funny? The mind. It’s like a computer.

NYR: Yeah, now I have to match it up —-

CB: Why? You see, I don’t have to do that. You’re a musician. I don’t think I’m a musician. What do you like on this album?

NYR: Most of it. I really like the first two on the second side… Do you really think this is your best album?

CB: Let me think about that for a second… Yeah, I would… I think so… But I’m not going to be that facetious. I really liked it. I felt that the baby got to be the baby.

By John Piccarella

He has a beef in his heart against society.