In 12 albums spread out over 13 years, Captain Beefheart has created a body of work that breaks most every rule in American music and results in something that couldn’t possibly be anything but American music.

Hey, man, take a look at these,” Captain Beefheart exclaims, holding some slides up to the bare bulb in his dressing rooms at the Beacon Theater in Manhattan. “These are some pictures!” Taken by a local freelancer, the slides show Beefheart standing at the microphone, blowing his soprano sax. “These were taken in 1969 at Ungano’s, the first time I came to New York” he exclaims, and it’s hard not to do a double-take. In 11 years, Beefheart appears to have aged hardly at all.

It figures, because the music of Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band is just as timeless. In 12 albums spread out over 13 years, Beefheart has created a body of work that breaks most every rule in American music and results in something that couldn’t possibly be anything but American music. And with rare exceptions – one album hoked up electronically by the producer, an unauthorized collection of out-takes, a Frank Zappa collaboration with too much Zappa and too little Beefheart – all his music could well have been released yesterday or 20 years ago or 20 years in the future. It sounds like nothing else on the market, stands outside all trends and movements and has earned Beefheart a following that’s kept him going all this time despite sales low enough to drive most people out of the music business.

Though he will admit to liking the work of Igor Stravinsky (“when he’s conducting it himself”), Howling Wolf (“because he’s a howling wolf, that’s why”) and Muddy Waters (“when he’s not playing with white people”), Beefheart will admit to having no musical influences, and it’s easy to see why. Still, there are rough analogies. His irregular, stop-and-go rhythms and cross-cutting guitars have something in common with blues. His horn work would be compatible with a free jazz band. The synthesizers add a futuristic touch. Then there’s his own hair-raising, seven-and-one-half-octave voice (which is so powerful it once shattered a new $1200 recording studio mike), and his stream-of-consciousness lyrics, the distinct flavour of which can be gleaned from a couple of song titles from Doc at the Radar Station, his current album: “A Carrot is as Close as a Rabbit Gets to a Diamond,” for example, or “Making Love to a Vampire With a Monkey On My Knee” (his most stunning new song).

After lasting years with virtually no recognition, Captain Beefheart is now being cited as a major influence by countless groups (most of them British) in the wake of the punk movement. Some are themselves cult heroes (Pere Ubu, Essential Logic, Young Marble Giants, Delta 5), but a few more are by now fairly well entrenched (Public Image Ltd., Gang of Four) and a couple could even be considered stars (the Clash, possibly Devo).

“You mean I’m the most stolen after,” Captain Beefheart chuckles when the subject comes up. “Actually I’ve never heard any of those groups. I mean, I hear myself enough, and listening to them would be like playing in my own vomit. I haven’t listened to my new album, and I like that album. So I’ve heard of all these groups, but I’ve never listened to them because it’s not original, I’ve already heard it.

“They’re following someone else and it’s that same old boom boom boom boom mother’s heartbeat beat, too, and we had enough of that a long time ago. If they wanna appreciate my art, fine, but why should they destroy themselves and build up harbored guilt? That’s not what art is for. Surely they’re upset if all they do is my music. The wrong way. They could never do it the right way because I already did it.”

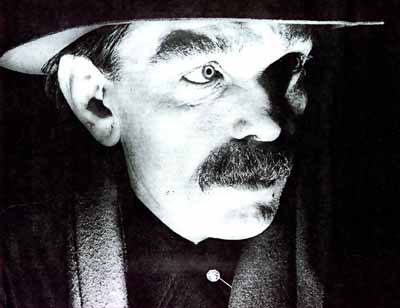

As Beefheart speaks, it is a few days before his Beacon Theater concert and a couple days after his appearance had salvaged an otherwise dismal installment of Saturday Night Live. He is holding forth in his hotel suite, alternately relaxed in an easy chair or pacing amongst the suitcases and bags on the floor, pulling cigarettes from three different packs according to what brand he feels like at the moment. He’s wearing brown corduroy pants, a brown khaki shirt and a red neck scarf that he also wears onstage. As always, there’s a clothespin clipped to his shirt. (He’s often asked why he wears it, and gives a different answer almost every time.) Though his comments on the other bands sound harsh, there’s a twinkle in his eye as he makes them; he speaks in sorrow as well as in anger. As in his songs, his speech follows its own logic, is full of puns and metaphors that don’t convey precise thoughts as much as they convey a mood or image or state of mind.

Don Van Vliet (his real name) was born and raised on Southern California’s Mojave Desert. Though he has since lived in Los Angeles and in the Northern California coastal town of Trinidad, today he and his wife Jan live back on the desert, in a house trailer in Lancaster. As a boy, he studied sculpture, which he still practices today; he is also an idiosyncratic painter whose art adorns several of his album covers, and he writes both poetry and novels.

But when Beefheart first went public with his creative work, he chose music as his vehicle because, “It’s more perishable; it’s more swirling, like smoke. It’s harder to sculpt music, too. But I’m glad I went at it that way, through a sculptor’s eyes, because it’s more fun. I do it as an irritation, that’s why I do music. I do it to irritate myself, because a little paranoia’s a good propeller.”

His recording debut consisted of two singles, neither of which sold, in 1966. His first album, Safe As Milk, was released the next year, followed by Strictly Personal in 1968. Both were relatively accessible blues-rock of a sort. But they were unusual enough that Beefheart was widely perceived as some manner of Sunset Strip acid guru – a complete misconception, because he has always condemned all drugs.

His reputation was made on 1969’s Trout Mask Replica, a staggering work produced by his old boyhood friend Frank Zappa (who’s often tapped into Beefheart for inspiration for his own music, which is to Beefheart’s as a Harold Robbins novel is to one by Melville) Though their relationship turned testy soon thereafter, Zappa was the first producer to grant Beefheart total freedom in the studio. Beefheart had written 25 new songs (including some instrumentals and some poems recited acappella) of such complexity that it took him eight months to teach them to the Magic Band.

Beefheart has always prepared each musician’s individual parts for each song on cassette. When each player has then mastered his lines, the band members rehearse the songs together. No deviation from Beefheart’s original music is permitted. Though sometimes criticized for what is perceived to be an authoritarian approach, Beefheart is quick to respond: “It wouldn’t be me otherwise, and so I wouldn’t do it. That’d be usurping my monetary expenditure to let them do their own parts; it costs money to have people play for you. I know what I want. I have to have that sound around me.”

On Trout Mask Replica he got what he wanted, and it is indeed an album of sculptured sound. But underneath the surface cacophony is a sure and delicate sense of rhythm, melody and harmony. The songs run a gamut from bawdy tall tales to ferocious protests (mostly concerning ecology, and man’s relationship to animals). Beefheart tears into them all with child-like enthusiasm, as if he was just discovering his own marvelous voice for the first time ever.

A few critics and musicians quickly hailed him as a genius, but record-buyers stayed away in droves. Lick My Decals Off Baby, The Spotlight Kid and Clear Spot were all nearly as startling as Trout Mask, though he seemed to be reaching out more to the audience with each new effort; all three suffered meager sales nevertheless. In 1974, with Unconditionally Guaranteed, Beefheart attempted to simplify and “go commercial” and even that failed. Except for a subsequent cameo role on Zappa’s Bongo Fury album and tour, Beefheart didn’t get to record again until 1978’s Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller).

With a track record like that, you might expect the man to have become bitter (earlier in his career, his contretemps with record companies and producers had been the stuff of legends). But Shiny Beast proved to be one of his lightest, most playful efforts. So it only follows now that with things going his way once again, Doc at the Radar Station would be a more somber album, one whose main themes are betrayal and claustrophobia.

“I’m real happy these days, and when I’m real happy it sounds more like… I mean, I’m mean, I’m irrascible. But this album is also hilarious, you know that. It’s a laughing stock. The reason it’s more serious is that my baby got more serious, my art baby that makes me do these things. And I thought, ‘I’ll get this thing exactly the way I heard it in a flash, period.’ And I did. Boom! Real quick. Hot right off the press. Turn it over, peel it back and just hope there aren’t too many garbage flanges. The baby just got mad at the fact that in all the things I’ve done – not all but a lot of them – there’s always been another cook trying to spoil my broth. I don’t like it and it won’t happen again.”

As he speaks, he’s gazing out the window at a black-and-yellow-checked umbrella someone is carrying on the street below. When car horns blare, he stops talking and cocks an ear to listen. Beefheart is fascinated with both sound and color in and of themselves. Asked what he’d do if his following grew to a mass audience and he had spending money, he thinks a moment and then answers, “I’d probably get an awful lot of canvas and an awful lot of black paint and see what I could do on a canvas with just black paint. I love black paint.”

Meanwhile, he’s now 40 and still a cult hero, a state of affairs that seems to faze him hardly at all. “I always think of those mooses with just the head up on a wall like that in a bar or something when I hear that word ‘cult’,” he cringes. “A shady bar. Shoddy and shady. I always think, ‘Who are you kidding?’ It sure seems like people take me too serious; I mean, I’d like to tickle them. I’m just doing what I’m doing and I’m having a good time at it.

“I mean, of course it’s good stuff; I’ll never do any bad stuff. I’m too smart. I’m an artist. I know I’m an artist because I didn’t sleep. We just came back from nearly a month in Europe and I slept eight hours the whole time. And I wrote four albums on this supposed hard jaunt of one-nighters around Europe. It was fun. I had a blast. Although I did worry about people I know that are virtually starving to death even though they’re working harder than ever before.

“I don’t know why all this sudden interest in me is happening, but it’s getting a little frightening. I think the planet is just a little more shakey, and oddly enough, when everything is getting hot like that, they like me.”

He glances back out the window and his eyes light up again as he adds, “The real amazing thing about New York to me is when they’re skating down the streets with one of those tape recorders. I don’t think they can skate down the street to my music. If they ever can, I wanna meet the person and get him in the band!”

-John Morthland, photo by Deborah Feingold