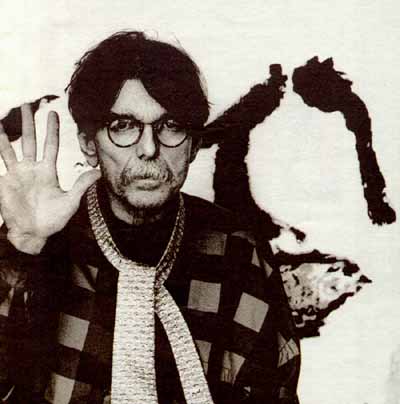

Don Van Vliet is probably the only full-time painter who used to be a mythical figure in music. Once Captain Beefheart, he is soon to exhibit in Brighton. Ben Thompson sent him a fax.

DON VAN VLIET lives in the small and beautifully named town of Trinidad in Northern California, up by the Oregon border, 135 ft from the ocean. He paints there. He is a painter of note – “Stand Up to Be Discontinued”, the second British exhibition of his work, arrives in Brighton in September to confound anyone who doubts this – but he used to be a painter of notes.

Until the early Eighties (and for ever more in the minds of those whose psychic foundations have been shifted by him), Don Van Vliet was Captain Beefheart. It would not be an exaggeration to call Beefheart the most mythical figure in all popular music. Except that his music was never what you would call popular. “For my whole life they’ve repeated to me that I’m a genius,” he observed ruefully, around the time he formally swapped his harmonica for a paintbrush. “But in the meantime they’ve also taught the public that my music is too difficult to listen to.”

Just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they’re not after you. Decades of critical histrionics have built up an aura of difficulty around the music of Captain Beefheart, and the wrong kind of difficulty at that. It’s not listening to it that is difficult, it’s not listening to it. Tumbleweeds of eccentric poetry on desert guitar winds; howling harmonica; nimble marimba; and a voice that can freeze-dry your soul one minute and tickle your ventricles the next. A voice that’s got so much grain you could make a loaf out of it. A voice that growls “I love you, you big dummy. Ha ha ha ha. Quit asking why.”

The strict separation between Beefheart the shaman / showman and Van Vliet the reclusive artist – he’s described it as “having a second life” – was largely a matter of tactics. Both the Captain and his wife Jan (an enigmatic and influential presence who crops up in old interviews, sitting on a sofa, reading a copy of Madame Bovary) realised that he would never be taken seriously as a painter so long as he was still making music. In fact, Beefheart was always a poet and a painter as much as a music-maker. His pictures adorned several of his album covers, and themes and words from his songs still reappear in his pictures. In any case, as he once wisely observed, “Talking about different art-forms is like counting raindrops: there are rivers and streams and oceans, but it’s all the same substance.”

Don Van Vliet makes a much better living from his paintings than he ever did from his records. And his decision to turn his back on his musical persona has had unrecognised beneficial consequences, wrapping the extraordinary Beefheart oeuvre in cling-film and preserving it unspoilt. Not for the Captain the grisly indignity of toilet-bound drug death or mortgage-motivated reunion tour. He is still alive and he is doing something else.

Meanwhile, his music awaits discovery by successive generations, and his life resists all attempts at demystification. Captain Beefheart went without sleep for a year and a half! His ears are three-and-a-half inches long! He once sold a vacuum cleaner to Aldous Huxley! Even if none of these stories turned out to be true, the allure of a life lived as myth would not be undermined.

BEEFHEART was born in 1941, in Glendale, California, and christened Don Vliet (the Van came later, it had transmission problems). Not deeply enamoured of formal education – “If you want to be a different fish, you’ve got to jump out of the school” – he seems to have acquired most of his early learning in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park Zoo. Here he met the celebrated Portuguese sculptor Augustinio Rodriguez, who was so impressed with his precocious talents that the child prodigy ended up on daytime TV, sculpting “images of nature” while the older master looked on. At the early age of 13, Vliet Jr. won a scholarship to study art in Europe, but his parents – convinced, their son later claimed, that to be an artist was not a manly occupation – decided to move him out of art’s way, with them, to the desert. This strategy proved felicitously unsuccessful.

At high school in the small, hot town of Lancaster, Don Vliet met the young Frank Zappa, with whom he shared a love for the then esoteric pleasures of West Coast R’n’B. By the early Sixties, Don and Frank were collaborating on various ludicrously ambitious film and opera projects in the small town of Cucamonga. From one of these – Captain Beefheart Meets the Grunt People – Don took his new name. They also recorded demos together as a band called The Soots, but these proved too much for the record companies of the day to cope with.

Zappa went to LA to form his Mothers of Invention, and Don ranged off in search of “desert musicians”. His first Magic Band – the first of the shifting agglomerations of extraordinary musicians via whom the sounds in his head would get out into the world – was a spring-heeled electric blues outfit, with Beefheart’s Howlin’ Wolf growl and punchy harmonica-playing much to the fore. They released a couple of singles on A & M Records, but Jerry Moss (the M to Herb Alpert’s A) thought their music “too negative” to be album-worthy, adding that one song in particular, “Electricity”, “wouldn’t be good for my daughter”.

When the song finally came out, Beefheart’s unearthly drawn out howl having broken a $1,200 studio microphone in the recording process, you could hear what Moss meant. The 1967 album Safe As Milk (Buddah) was to be the first of many triumphant Beefheartian re-emergences from semi-retirement; his sound palette now expanded to pinks and oranges as well as the blues, his unique ecological sensibility already firmly established (the title was not, as widely supposed, a drug reference, but a warning of the dangers of Strontium 90 in breast milk).

Unfortunately, the pattern of Beefheart’s dealings with the music business was already set, too. The band had to pull out of playing the Monterey Pop Festival (which helped make stars of Jimi Hendrix and The Who among others), because their then lead guitarist, a certain Ry Cooder, didn’t think they were ready. Their next album, Mirror Man, recorded around the same time as Safe As Milk, was not released until three or four years later, while its successor, Strictly Personal (Blue Thumb, 1968), did come out straight away, but only after manager Bob Icrasnow had done his best to ruin it by adding absurd “far-out” hippie phasing effects while Beefheart was away on tour in Britain.

Zappa, who by now had his own record company, offered Beefheart the chance to make a record without such interference. Beefheart grabbed it with both hands, and the result was Trout Mask Replica (Straight, 1969), a revolutionary 28-pan song-cycle which still sounds like both the most modem and the most primitive music ever made. The whole thing – apocalyptic blues, avant-garde hoedowns, sung and spoken poems, impossibly intricate instrumentals was, Beefheart claimed, composed at the piano in eight and a half hours (why did it take so long, Rolling Stone journalist Langdon Winner asked jokingly. Beefheart replied that he “hadn’t played piano before and had to work out the fingering”).

It is clear that the Captain was not an easy man to work for. Various members of the Trout-era Magic Band – Beefheart’s “cousin”, the Mascara Snake, drummer John “Drumbo” French, bassist Rockette Morton, guitarists Antennae Jimmy Semens and the outlandishly tall Zoot Horn Rollo – have expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of credit they received. Last year, part-time record-shop manager Bill Harkleroad (formerly Zoot Horn Rollo – Beefheart owns the copyright to all stage names) described him as “Manson-esque”. “People don’t like to be used as paint,” Van Vliet shot back. “If they’re going to be used by me, that is the only way they’re going to be used.” Beefheart cares about trees, though. While Trout Mask Replica was being rehearsed at his house, Beefheart pestered the record company to pay for a tree-surgeon to calm surrounding oaks and cedars, in case they might be frightened and fall over. Straight Records refused, but Beefheart sent them the bill anyway.

OVER the next three albums, the Magic Band’s fiendishly complex web of sound unravelled into progressively more recognisable shapes. Lick My Decals Off Baby (Reprise, 1970) was perhaps the most life-enhancingly libidinous record of all time, with the recently married Captain proclaiming “I Wanna Find Me a Woman to Hold My Big Toe Till I Have to Go”. Beefheart threatened, – or was that promised? – in The Spotlight Kid (Reprise, 1971) to “grow fins, and go back in the water again”.

All the time, the beat was getting less jagged, but the spirit was just as free. Clear Spot (Reprise, 1972) was Beefheart’s most accessible and in some ways most magical record yet. As well as the lovely “My Head is My Only House Unless it Rains”, it contained, in the immortal “Big Eyed Beans From Venus”, the nearest thing there is to an archetypal Captain Beefheart moment: “Mr Zoot Horn Rollo – hit that long, lunar note, and let it float”. It was not a hit.

In revenge, Captain Beefheart sold out. The sleeve of Unconditionally Guaranteed (Virgin, 1974) pictures him wishfully clutching wads of banknotes. Twenty years on, this sounds like an underrated pop record. At the time it was, to put it mildly, a let-down. The disgruntled Magic Band swanned off to form the ill-fated Mallard (a dead duck), leaving Beefheart to make the deplorable Bluejeans and Moonbeams with a load of session musicians. He later urged anyone who bought either of these records to return to the shop and try to get their money back.

The Captain was down, but not out. Alter recharging his batteries hooking up with Frank Zappa again, he formed a new Magic Band, built around guitarist Jeff Tepper, and eventually released Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) (Virgin, 1978). This was a sumptuous return to his best, with a seductive new Latin shuffle. The wired and abrasive Doc at the Radar Station (Virgin, 1980) followed, to show those ungrateful punks and new-wavers who was boss. Ice Cream for Crow (Virgin, 1982) was, in retrospect, a suitably restless and openended swan-song, but it had at least one prophetic mo-ment in “The Past Sure Is Tense”.

Since then, the Captain has retreated behind a veil of painterly swank, with a little help from friends like crockery specialist Julian Schnabel and German expressionist A R Penck (who, with the phrase “Re-achieving naivety”, came as close as anyone to pinning down what it is that both Van Vliet and Beefheart are up to). When he had his first British exhibition at the prestigious Waddington Galleries in Cork Street, London, in 1986, fans of his music gathered in a mixture of pleasure and puzzlement. They will no doubt do the same at this one, perhaps venturing the time-honoured opinion – in view of the increasingly sombre tone of Van Vliet’s work, and the decreasing number of funny animals in it – that they prefer his early stuff. Fans of his paintings will speak of Van Gogh and Franz Kline and scrabble through their pockets for the five figures’ worth of loose change required to buy one.

A lot of people, myself included, get the same joy from the best of Beefheart’s paintings as they do from his music. But what Don Van Vliet does in art already has what the catalogues call a “distinguished aesthetic history” – which is not, of course, something to be ashamed of. And what he did in music was totally new. This is why people will always tend to be less interested in the development of his technique as a painter than in how he learnt to play the harmonica by holding it out of his parents’ window. In one sense this must be frustrating for him; in another, it leaves him free to paint in peace.

AT MICHAEL WERNER, his New York gallery, they said that their man preferred not to talk on the phone, because he was likely to ramble on for hours and then not be able to concentrate on his painting. A brief exchange of faxes was agreed upon as the best solution. It proved – at least in terms of the unyielding pithiness of the responses Van Vliet dictated for his wife Jan to type up – cruelly successful. He asked for the answers to be printed verbatim.

What are the distinctive characteristics of your speaking voice, and what are you wearing?

I’m wearing black accordion baggy type pants that are held up by black Oxfords. I am wearing a buffalo plaid shirt, red and black squares. I sound partially interrupted by chewing on sunflower seeds – beautiful, sunflower – black and white.

Is there anything particular on your mind today?

The thought of diagnosing your question and then sifting through what I think about it.

The idea I have of where you live is of a very isolated place – is that right? Please describe it.

A painted birdcage above a hack-saw ocean with lovely redwood stalks with zillions of raindrops, falling.

Did the pressure of people being interested in you make you move there, or would you have lived somewhere like that anyway?

I would have lived somewhere like this anyway, but a prod of the feet of humans made me do it sooner.

Does living where you do make you feel cut off from the world, or more able to see it clearly?

Cut off just enough to feel well tailored.

Do you have a working routine, and if so, what is it?

Life.

Is it possible to work too hard, and would you if you could?

Answering your question as asked – I would not like calluses, I would rather have the hands of a fine painter.

What was the first picture you can remember painting and how do you feel about it now?

It probably doesn’t even remember me.

Who are the other painters who have given you the most pleasure and inspiration, and why?

Inspiration is a crutch word.

Someone told me you had had some trouble with an allergy to paint Is that true? I hope not. If so, did it change how you feel about what you do?

What?

Do you find it more satisfying to express yourself in paint than in sound? What are the most striking differences between the two forms of endeavour?

One you can physically drown in, being paint. The other you can mentally drown in. I prefer swimming in paint.

Do you still make music for your own pleasure, and do you have any interest in your musical legacy?

I’m not doing music now and it’s personal. Legacy sounds more like the fitting of a boot and I hope they don’t fit me with any bootlegs or stupid compilation albums.

Do you consider yourself to have a special way with words?

Funny you should ask, you seem to be of good hearing.

Have you ever thought you might become a writer?

What?

Are there any animals for which you have a particular fondness, and what do you especially like about them?

The inhuman quality of animals.

Is “man” the best or the worst part of nature? If you ever go to a place where there are a lot of people, do they make you feel hopeful or frightened?

They make me miss animals.

If you could listen to a song or look at one picture, which would it be?

Art is as close as you can get to perfection without getting caught up in the wink.

Ben Thompson, 1994