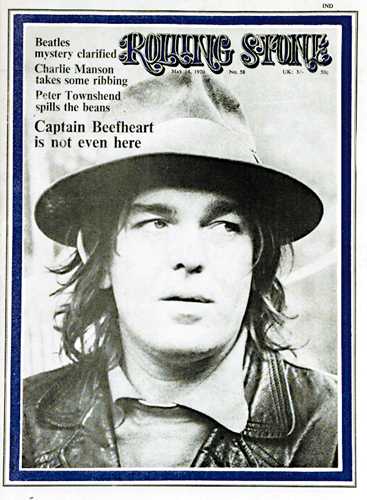

“Uh oh, the phone,” Captain Beefheart mumbled as he placed his tarnished soprano saxophone in its case. “I have to answer the telephone.” It was a very peculiar thing to say. The phone had not rung.

Beefheart walked quickly from his place by the upright piano across the dimly lit living room to where the telephone lay. He waited. After ten seconds of stony silence it finally rang. None of the half dozen or so persons in the room seemed at all surprised by what had just happened. In the world of Captain Beefheart, the extraordinary is the rule.

At age 29, Captain Beefheart, also known as Don Van Vliet, lives in seclusion and near poverty in a small house in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles. Although it appeared on several occasions in the past that he would rise to brilliant stardom as a singer and bandleader, circumstances have always intervened to force him into oblivion. In his six years in the music business he has appeared in public no more than 25 times.

Since virtually no one has ever seen him play, stories about his life and art have taken on the character of legend, that is, of endless tall tales. People who saw him at the Avalon Ballrooom in San Francisco three years ago will now tell you, “I heard that he’s living in Death Valley somewhere.” or “Didn’t he just finally give up?” But there is considerably more to the man than the legend indicates.

The fact is that Don Van Vliet is alive, healthy, and happy, and putting together a new Magic Band to go on tour soon. As his recent album “Trout Mask Replica” testifies he is one of the most original and gifted creators of music in America today. If all goes well, the next six months should see the re-emergence of Captain Beefheart’s erratic genius into the world and the acceptance of his work by the larger it has always deserved.

The crucial problem in Beefheart’s career has been that few people have ever been able to accept him for what he is. His manager. musicians, fans, and critics listen to his incredible voice, his amazing lyrics, his chaotic harp and soprano saxz, and uniformly decide that Beefheart could be great if he would only (1) sing more clearly and softly (2) go commercial, (3) play blues songs that people could understand and dance to. “Don, you’re potentially the greatest white blues singer of all time.” his managers tell him, thinking that they are paying him a compliment. Record companies eagerly seek the Beefheart voice with its unprecedented four and one half octave range. They realize that the man can produce just about any sound he sets his mind to and that he interprets lyrics as well as any singer in the business. Urging him to abandon the Magic Band and to sing the blues with slick studio musicians, record producers have always been certain that Don Van Vliet was just a hype away from the big money.

But Beefheart stubbornly continues what he’s doing and waits patiently for everyone else to come around. He has steadfastly refused to leave the Magic Band or to abandon the integrity of his art. “I realize,” he says, “that somebody playing free music isn’t as commercial as a hamburger stand. But is it because you can eat a hamburger and hold it in your hand and you can’t do that with music? Is it too free to control?”

Beefheart’s life as a musician began in the town of Lancaster nestled in the desert of Southern California. He had gone to high school there and become the friend of another notorious Lancasterian, Frank Zappa. In his late teens Don Van Vliet listened intensively to two kinds of music – Mississippi Delta blues and the avant-garde jazz of John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. Although he was attracted to music and played briefly with a rhythm and blues group called the Omens, he did not yet consider music his vocation. He enrolled at Antelop Valley Junior College in 1959 as an art major, and soon grew suspicious of books and dropped out. For a brief while he was employed as a commercial artist and as a manager of a chain of shoe stores. “I built that chain into a thriving, growing concern,” he recalls, “Then as a kind of art statement I quit right in the middle of Christmas rush leaving the whole thing in chaos.” In the early Sixties Don Van Vliet moved to Cucamonga to be with Frank Zappa who was composing music and producing motion pictures. It was at about this time that Van Vliet and Zappa hatched up the name Captain Beefheart, “But don’t ask me why or how,” Beefhaert comments today. The two made plans to form a rock and roll band called the Soots and to make a movie to be named “Captain Beefheart Meets The Grunt People”, but notheing ever came of either project. In time Zappa left for Los Angeles and formed the Mothers. Beefheart returned to Lancaster and gathered together a group of “desert musicians.” In 1964 the Magic Band was ready to begin playing teen age dances in its home town.

The one stage appearance of the first Beefheart ansemble was bizarre to the point of frightening. All members of the magic Band were dressed in black leather coats and pants with black high heel boots. The lead guitar player had a patch over one eye and long dangling arms that reached from his shoulders to half way bleow his knees. At a time that long hair was still a rarity, the Captain sported long dark locks down to his waist. It was simply outrageous.

The band was an immediate sensation in Lancaster and very soon its fame began to spread throught southern California. Beefheart’s brand of abrasive blues-rock was truly a novelty to young listeners in 1964. Record companies interested in the new sound began to take notice. In mid 1964 Beefheart entered into the first of a long series of disastrous agreements with record producers.

His first release on A&M was a new version of “Diddy Wah Diddy” made popular by Bo Diddley. It featured his own style of frantic harp playing and an incredibly “low down” voice hitting notes at least half an octave lower than the lowest notes ever sung by any other rock performer. The record was a hit in Los Angeles and for a while it appeared that Beefheart was going to be a brilliant success in the music business.

But it was not to be. Beefheart recorded an album of new music and took it to Jerry Moss of A&M (Alpert and Moss). Moss listened to the songs – “Electricity,” “Zig Zag Wanderer,” “Autumn’s Child,” etc. – and declared that they were all “too negative.” He refused to release the album. Beefhaert was crushed by this insensitivity and abruptly quit playing. A&M released the reamining single it had in the can. The words to “Frying pan” now seemed strangely prophetic: “Go down town/ Yuo walk around/ A man comes up, says he’s gonna put you down/ You try to succeed to fulfill your need/ Then a car hits you and people watch you bleed/ Out of the frying pan into the fire/ Anything you say they’re gonna call you a liar.”

The record went nowhere and neither did Beefheart. For almost one year he lived in retirement back in Lancaster.

The second break in Beefheart’s career arrived in 1965 when producer Bob Krasnow of Kama Sutra agreed to release the same material that A&M had rejected. Beefheart reassembled the Magic Band and returned to record the twelve cuts of “Safe As Milk” (Buddah BDS 5001), an album which is still one of the forgotten classics of rock and roll history. Even though the album had been delayed for a year, it was still far ahead of its time. It featured the unmistakable Beefheart style of blues and bottleneck guitar, the first use in popular music of an electronic device called the theremen, [sic] and the first effective synthesis in America of rock and roll and Delta blues.

For the first time also, Beefheart was able to demonstrate the power and range of his voice. On one song, for example, Beefheart’s vocal literally destroyed a $1200 Telefunken microphone. Hank Cicalo, engineer for the sessions, reports that on the song “Electricity” Beefheart’s voice simply wouldn’t track at certain points. Although a number of microphones were employed, none of them could stand the Captain’s wailing “EEEE-Lec-Triccc-ittt-EEEEEEEE” on the last chorus. This, incidentally, can be heard on the record.

With an excellent album under his belt Beefheart felt confident enough to go on the road. In early 1966 he went on a tour of England and Europe where Safe As Milk had attracted considerable attention. When he returned to the States he played gigs at the Whiskey A-Go-Go in Los Angeles and the Family Dog in San Francisco. Well received in the burgeoning psychedelic rock scene, it seemed once again that Beefheart was on the verge of success. The Magic Band was scheduled to play a gig at the Fillmore and to appear at the Monterey Pop Festival, both of which could have been springboards to the top.

Then disaster struck. Beefheart’s lead guitar player suddenly quit the band leaving a gap which could not be filled. The unusual nature of Beefheart’s songs make it necessary for him to spend months teaching each new musician his music. The departure of the lead guitar destroyed Beefheart’s chances in the San Francisco scene. The Monterey Pop Festival went on without him. Those who attended it never knew what they had missed.

From this point in the story, events become even more chaotic and difficult to unravel. Beefheart returned to Los Angeles and tried to put together a new band and a new set of songs. His producer, Bob Krasnow, was to arrange the second Beefheart album on Buddah. According to sources in the Los Angeles record industry, Krasnow deliberately allowed the option on Beefheart’s contract to expire. When this happened he signed Beefheart to a personal contract and then sold the rights to Beefheart’s next album to both Buddah Records and MGM. Tapes of the album were then made at two different studios, apparently at the expense of both companies. When the sessions were finished in the summer of 1968 Beefheart left for a second tour of Europe.

In Beefheart’s absence Bob Krasnow released the album Strictly Personal under his own label, Blue Thumb, without Beefheart’s approval. As lawsuits filled the air, Beefheart himself was left in bewilderment. The record had been electronically altered through a process called phasing which totally obliterated the sound which he had been striving to put down. “That’s the reason that album is as bad as it is,” he sighs when asked about the incident. “I don’t think it was the group’s fault. They really played their ass off — as much as they had to play off.”

But despite the electronic and legalistic hanky panky surrounding its production, Strictly Personal is an excellent album. The guitars of the Magic Band mercilessly bend and stretch notes in a way that suggests that the world of music has wobbled clear off its axis. Beefheart’s singing is again at full power. In songs like “Trust Us” and “Son of Mirror Man — Mere Man” it sounds as if all the joy and pain in the universe have found a single voice. Throughout the album the lyrics demonstrate Beefheart’s ability to juxtapose delightful humor with frightening insights — “Well they rolled around the corner / Turned up seven come eleven / That’s my lucky number, Lord / I feel like I’m in heaven.”

The unfortunate fact about the second album was that few people were able to get into it. Apparently, the combination of Beefheart’s musical progress and Krasnow’s electronic idiocy made the album too much for most listeners to take. Strictly Personal sold poorly and did nothing to advance the band’s popularity.

To this day there exists a strange love/hate relationship between Beefheart and Krasnow over the record. Krasnow claims that Beefheart still owes him $113,000 and that as a result of Beefheart’s disorganized way of handling money, he has been thrown in jail twice. Beefheart, on the other hand, usually cites Krasnow as a charlatan and pirate – the man most responsible for destroying his career. At other times, both men speak of each other with genuine respect, sympathy and affection. “I’d really like to have him back with me,” Krasnow said recently. “He’s actually a good man,” Beefheart will tell you.

Most of the Captain’s relationships with those close to him are of this sort. Everybody’s a despicable villain one day, a marvelous hero the next.

The current focus of Beefheart’s love/hate dialectic accounts for much of his current activity and inactivity. This time the prime protagonist is Frank Zappa.

Zappa has always had a great admiration for his old friend from Lancaster – an admiration often bordering on worship. Like so many of those around Beefheart, Zappa considers the man to be one of the few great geniuses of our time. When the smoke had cleared from the Blue Thumb snafu, Zappa came to Beefheart and told him that he would put out an album on his label, Straight Records. Whatever Beefheart wanted to do was O.K. and there would be no messing around with layers of electronic bullshit. The result was Trout Mask Replica, an album which this writer considers to be the most astounding and most important work of art ever to appear on a phonograph record.

When Beefheart learned of the opportunity to make an album totally without restrictions, he sat down at the piano and in eight and a half hours wrote all twenty-eight songs included on Trout Mask. When I asked him jokingly why it took that long, he replied, “Well, I’d never played the piano before and I had to figure out the fingering.” With a stack of cassettes going full time, Don banged out “Frownland,” “Dachau Blues,” “Veterans’ Day Poppy,” and all of the others complete with words. When he is creating, this is exactly how Don works — fast and furious.

“I don’t spend a lot of time thinking. It just comes through me. I don’t know how else to explain it.” In his box of cassettes there are probably dozens of albums of Trout Mask Replica quality or better. The trouble is that once the compositions are down it takes him a long time to teach them to his musicians. In this case it took almost a year of rehearsal.

Trout Mask Replica is truly beyond comparison in the realm of contemporary music. While it has roots in avant-garde jazz and Delta blues, Beefheart has taken his music far beyond these influences. The distinctive glass finger guitar of Zoot Horn Rollo and steel appendage guitar of Antennae Jimmy Semens continues the style of guitar playing which he has been developing from the start. It is a strange cacophonous sound — fragmented, often irritating, but always natural, penetrating and true. Beefheart himself does not play the guitar, but he does teach each and every note to his players. The same holds true for the drums. Don does not play the drums but has always loved unusual rhythms and writes some of the most delightful drum breaks in all of music.

On Trout Mask Replica Beefheart sings 20 or so of his different voices and blows a wild array of post-Ornette licks through his “breather apparatus” — soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone and musette. When Beefheart inhales before taking a horn solo, all of the oxygen in the room seems to vanish into his lungs. Then he closes his eyes, blows out and lets his fingers dance and leap over the keys. The sound that bursts forth is a perfect compliment to his singing — free, unrefined and full of humor.

Trout Mask is the perfect blend of the lyrics, spirit and conception that had been growing in Don Van Vliet’s mind for a decade. Although it is a masterpiece, it will probably be many years before American audiences catch up to the things that happen on this totally amazing record.

For the first time in his career, Beefheart was entirely satisfied with his album. Zappa had made good his promise to give him the freedom he required and in fact issue the record in a pure and unaltered form. Nevertheless, the Beefheart/Zappa relationship is presently anything but an amicable one. Beefheart claims that Zappa is promoting Trout Mask Replica in a tasteless manner. He does not appreciate being placed on the Bizarre-Straight roster of freaks next to Alice Cooper and the GTO’s. He constantly complains that Straight Records’ promotion campaign is doing him more harm than good.

Straight Records on the other hand claims that Beefheart’s problems are all of his own making. He refuses to go on tour and procrastinates about making a follow-up album. “What can we do?” a Straight P.R. man asked me. “Beefheart is a genius, but a very difficult man to work with. All we can do is try to be as reasonable as possible.” Straight’s brass recall that during the recording of the parts of Trout Mask which were done in Beefheart’s home, Don Van Vliet asked for a tree surgeon to be in residence. The trees around the house, he believed, might become frightened of the noise and fall over. Straight refused to hire the tree surgeon, but later received a bill for $250 for such services. After the sessions were over Beefheart has hired his own tree doctor to give the oaks and cedars in his yard a thorough medical check up — his way of thanking them for not falling down.

In another classic story of this sort, Herb Cohen of Straight recalls that one day he noticed that Beefheart had ordered 20 sets of sleigh bells for a recording session. Cohen pointed out that even if Frank Zappa and the engineer were added to the bell ringing this would account for only 14 sleigh bells — one in each hand of the performers. “What are you going to do with the other six?” he asked. “We’ll overdub them,” Beefheart replied.

The fact of the matter seems to be that precisely the same qualities of mind which make Beefheart such an astounding poet and composer are those which make it difficult for him to relate to Frank Zappa or anyone else in the orthodox music business. Like many notable creative spirits, Beefheart’s personality is not geared to the efficient use of time or resources. For this reason and for the reason that he has often been burned by the industry, Beefheart is very suspicious of those who try to influence the direction his career takes. To see why he has such continual trouble adjusting to the practicalities of his vocation, it will do well for us to look briefly at the incredible story of Beefheart’s life before he became a musician.

Don Van Vliet was born in 1941 in Glendale, California, to normal middle-class parents. He grew up without problems as any child would in Glendale — until the age of five. It was then that he decided that civilized American life was a gigantic fraud. Don noticed that this society had established a destructive tyranny over nature; over all the animals and plants of Earth. He also became aware of the fact that America extended this tyranny over each man and that it was apparently out to include him in “the great take over.” They wanted to teach him proper language, social rules, arithmetic and all of the other noxious techniques required to live in this country. Young Don suddenly rebelled and refused to go along.

Looking back on it now Beefheart recalls one day of enlightenment. “My mother, who I called ‘Sue’ rather than ‘mother’ because that was her real name, was walking me along a path to school — the first day of kindergarten. We came to an intersection and she walked right out into the way of a speeding car. I reached up with both hands and pulled her out of the way. She could have killed us both. It was then that I thought to myself, ‘And she’s taking me to school.'” So Don did not attend school, at least not regularly. Instead he took up sculpting all the birds of the air, fish in the sea and animals on the land. Because he refused to come out for dinner, his parents were obliged to slide his meals under the bedroom door to him. It was Don’s belief that he could re-establish ties to everything natural through the art of sculpture.

Soon he was good enough at what he was doing to attract the attention of professional Los Angeles artists. One day during a visit to the Griffith Park Zoo he met and befriended Augustino Rodriquez, the famous Portugese sculptor. Together they did a weekly television show in which Don would sculpt the images of nature’s art while Mr. Rodriquez looked on.

Understandably, Don’s parents were concerned about the unusual inclinations of their son. When at age thirteen he won a scholarship to study art in Europe, they took strong steps to discourage him. “My parents told me all artists were queers,” Beefheart recalls. “They moved me to the desert, first to Mojave and later to Lancaster.”

But even though Don’s life as a sculptor had ended, he never gave up the vision of art and nature that he had discovered in life. Neither did he forsake the wonderfully unstructured consciousness with which he had been born. “I think that everybody’s perfect when they’re a baby and I just never grew up. I’m not saying that I’m perfect, because I did grow up. But I’m still a baby.”

Beefheart still believes that in nature all creatures are equals. Man in his perversity forgets this and builds ridiculous hierarchies and artificial systems to set himself apart from his roots. “People are just too far out. Do you know what I mean? Too far out—far away from nature.” He still sets out sugar for the ants, creatures that he considers most similar to man in their mode of life. “If you give them sugar,” Beefheart contends “they won’t have to eat the poison.”

In songs like “Wild Life,” “My Human Gets Me Blues,” and “Ant Man Bee” Beefheart presents with great subtlety the truths which students of ecology are just now beginning to recognize. “Now the bee takes his honey/ Then he sets the flower free/ But in God’s garden only man ‘n the ants/ They won’t let each other be.” It is entirely possible that it is in this area that Beefheart will eventually attract a wide audience. If those who are delving into ecology would listen carefully to Trout Mask Replica, the Another definite carryover from Beefheart’s unusual childhood can be seen in the marvelous quality of his lyrics and poems. Since young Don Van Vliet decided that civilization was a trap, he refused to use civilized English in a linear, logical way and learned the entire language as a vast and amusing game. As a result, virtually everything that he says or writes turns out to be poetry. In a conversation with Beefheart the entire structure of verbal communication explodes. A barrage of puns, rhymes, illogicalities, absurd definitions, and unending word play fills the dialogue with a wonderful confusion.

“You can’t make generalizations,” he said to me during one such conversation.

“Why not?” I replied, taking the bait.

“I wonder if anyone’s ever made General I. Zation?” he continued, this time apparently talking about the sex life of some unknown military hero. “If all the generals came in right now, I bet they’d bring those IZATIONS with them.” Could he be talking about some secret weapon? There was no time to think about it, for in a flash Beefheart had gone on to a discussion of people who were “trying to put bandaids on The Flaw.” The Flaw?

I have seen several occasions in which visitors to Beefheart’s home have totally freaked because of this manner of talking. Not many people, after all, feel comfortable listening to the English language collapse before their very ears.

All of this wonderment, of course, comes through very clearly in Beefheart’s lyrics. In “My Human Gets Me Blues,” for example, the Captain sings, “I saw yuh dancin’ in your x-ray gingham dress/ I knew you were under duress/ I knew you under your dress.” One way of getting into songs like this is to understand that Beefheart is primarily fascinated with the sounds of words and their many ambiguities rather than the explicit meaning of terms. He believes that all truth comes from playing rather than from The secret is, however, that they can be communicated only after the listener surrenders his neurotic reliance on words and established forms. “I’m trying to create my own language,” Beefheart observes, “a language without any periods.”

In his discouragement with the music business Beefheart has now turned much of his energy to writing as an outlet for his creative demon. The closets of his house are strewn with thousands upon thousands of poems and at least five unpublished novels. The song “Old Fart at Play” from Trout Mask Replica is a tiny excerpt from a long novel of the same name which Beefheart hopes to publish soon.

The formlessness and intensity of Beefheart’s music have often led people to conclude that he is merely another product of the drug culture. Sadly, much of the promotion material on him in past years has implied that he is the king of the drug heads and hip freaks. Nothing could be further from the truth. Don Van Vliet does not use drugs and does not allow members of the Magic Band to do so either. Like his friend Frank Zappa, Beefheart admonishes everyone to stay away from LSD, speed and marijuana. The In my conversation with the man, Beefheart would often smile broadly and tilt his head far back on his neck and say, “You know, I’m not even here. I just stick around for my friends.” Moving his hand up and out from his temple and wiggling his fingers (the Beefheart “Far Out” sign) he would then say, “You not even here either. You know that. Don’t kid yourself. You just stick around for your friends too.”

Like Socrates, Beefheart believes that everyone knows everything he needs to know already. What he tries to do is to make them realize this. Most people, he reports, fight it every inch of the way. They refuse to be free even when they see what it’s like. “They just have too much at stake.”

The absolutely boundless character of Beefheart’s mind has taken him into investigations of extra-sensory perception, clairvoyance and even reincarnation. In addition to his ability to answer the phone before it rings, Beefheart is apparently able to foretell parts of the future. On all of my visits to his house in the San Fernando Valley, Beefheart told me he knew in advance that I was coming. On one occasion he was able to prove it to me by showing that he’d put on “The Florsheim Shoe” and bright red In order to pursue the possibilities of this previous existence, the Captain has recently begun painting again. Like everything else he does, his paintings are simply astounding. During one of our conversations he went to a two foot tall stack of poster paper and pulled out one of his recent works. Holding it under his chin and peering over it at me, Beefheart asked, “Well, what do you see?” I stared into the spots and blobs of yellow, green and red and had to confess that the painting said nothing to me.

At present the Captain stands at a crucial turning point. On the face of it everything seems to be in his favor. His new Magic Band is probably the best he’s ever had and may be one of the best in the country. He has recently added drummer Art Tripp, formerly of the Mothers of Invention, who provides exactly the right blend of rhythmic novelty and imagination to the groups’ sound. Zoot Horn Rollo and Rockette Morton, musicians that Beefheart taught from scratch, have reached musical maturity and are eag Beyond this, Beefheart now has around him a group of associates that he should be able to trust. His new manager, Grant Gibbs, is both honest and thoroughly sensitive to the special needs and foibles of his artist. Previously and unbiased observer of Beefheart’s career, Mr. Gibbs is now trying to untangle the web of contractual knots which the Magic Band had stumbled into over the years. Although Beefheart thinks otherwise, Straight Records is probably giving him as good and forthright a deal as he’d find.

But who knows? Perhaps 1970 will be the year that we finally catch a glimpse of the man behind the Trout Mask. Maybe this will be the year that all of us can experience the amazing wisdom and humor that Captain Beefheart has in his grasp. Clearly though, it’s strictly up to him.